Tennis Hits the Books

In celebration and observation of Women’s History Month, each “Tennis Hits the Books” post in March will focus on Women’s Tennis. Since tennis is the subject of this blog, it would be “off-brand” to write about women competing in any context or capacity. To kick that theme off, last week I wrote about Venus Envy by Jon Wertheim. That book covered the WTA professional circuit in the year 2000. Ladies of the Court by Michael Mewshaw is the natural follow up. Mewshaw’s book is also a “year in the life” account of the WTA tour as it was in the year 1991.

If I had to pick one word to describe Ladies of the Court it would be “lurid.” “Sordid” is a close second selection. Perhaps I should have anticipated that, given that the subtitle is “Grace and Disgrace on the Women’s Tennis Tour.” After reading Ladies of the Court, I really want to believe is that we, as society and a tennis community, have come a long way, baby. Unfortunately, that appropriates the advertising catch phrase of the cigarette brand that financed the early stages of the WTA tour. In Ladies of the Court, the Virginia Slims title sponsorship was unraveling. Spoiler alert: Cigarettes are bad for you. Additionally, as the USTA incessantly reminds us as of late, tennis is a healthy sport. Sponsorship by a tobacco company was incongruous.

As another side note, in “Revisiting Donald Dell,” I wrote about how Donald Dell has been turning up in almost every single book that I read. I am happy to report, that was absolutely no mention of Donald Dell in Ladies of the Court. Instead I was confronted by his brother, Dick Dell, who is also an agent at ProServ. Dick Dell appears repeatedly throughout the book as he was Gabriella Sabatini’s agent in 1991.

Sabatini epitomizes the players in this era of women’s professional tennis in many ways. She was beautiful and elegant and highly courted by corporate sponsors. Like so many other women players in this era, she dropped out of school when she turned professional at age 13. As a personal observation, I don’t think that is a good age to stop the intellectual development of a person. There is an amusing account in the book where Sabatini missed her cue during a trophy presentation. One observer remarked that she didn’t know two words of English. The reply was that she didn’t know all that much Spanish either. To say that Sabatini was not a dynamic player to interview is an understatement.

Seizing on bizarre side references is one of the hallmarks of this site. None is stranger than a poem about Sabatini written by Clive James. James is an Australian born writer with a long list of published books to his credit. His poem, “Bring Me the Sweat of Gabriela Sabatini, is one of the strangest things that I have encountered to date. There is a fairly high probability that there will be a future post dedicated entirely to that work, including analysis of what it means for women’s tennis. I am shocked to find myself considering writing about poetry.

Legendary coach Dennis Van Der Meer was frequently consulted by Mewshaw and has recurring quotes and observations interspersed throughout the book. Some of his comments don’t resonate well under modern scrutiny. Specifically he observed that the women players are generally emotionally fragile and unstable. He also asserted that a very high number of professional players were engaged in sexual relationships with their male coaches. I spent much of the book mentally trying to reconcile his comments as simply a reflection of the culture at the time. Toward the end of the book, I experienced a sudden revelation that there is a very good possibility that he wasn’t wrong about anything he said.

Ladies of the Court and Venus Envy when read together provide some interesting before and after contrasts between some of the players who figure prominently in both books. In Ladies of the Court, Monica Seles was a verbally effusive and fairly shallow teenager rising into dominance. She comes off as a spoiled brat who was not well liked by the other players. A lot transpired for Seles between Ladies of the Court in 1991 and Venus Envy in 2000. Specifically, her horrific on-court stabbing by a deranged Steffi Graf fan. The contrast of how Seles was presented in the two accounts makes is obvious that she grew up significantly between the two books. Given the circumstances, how could she not.

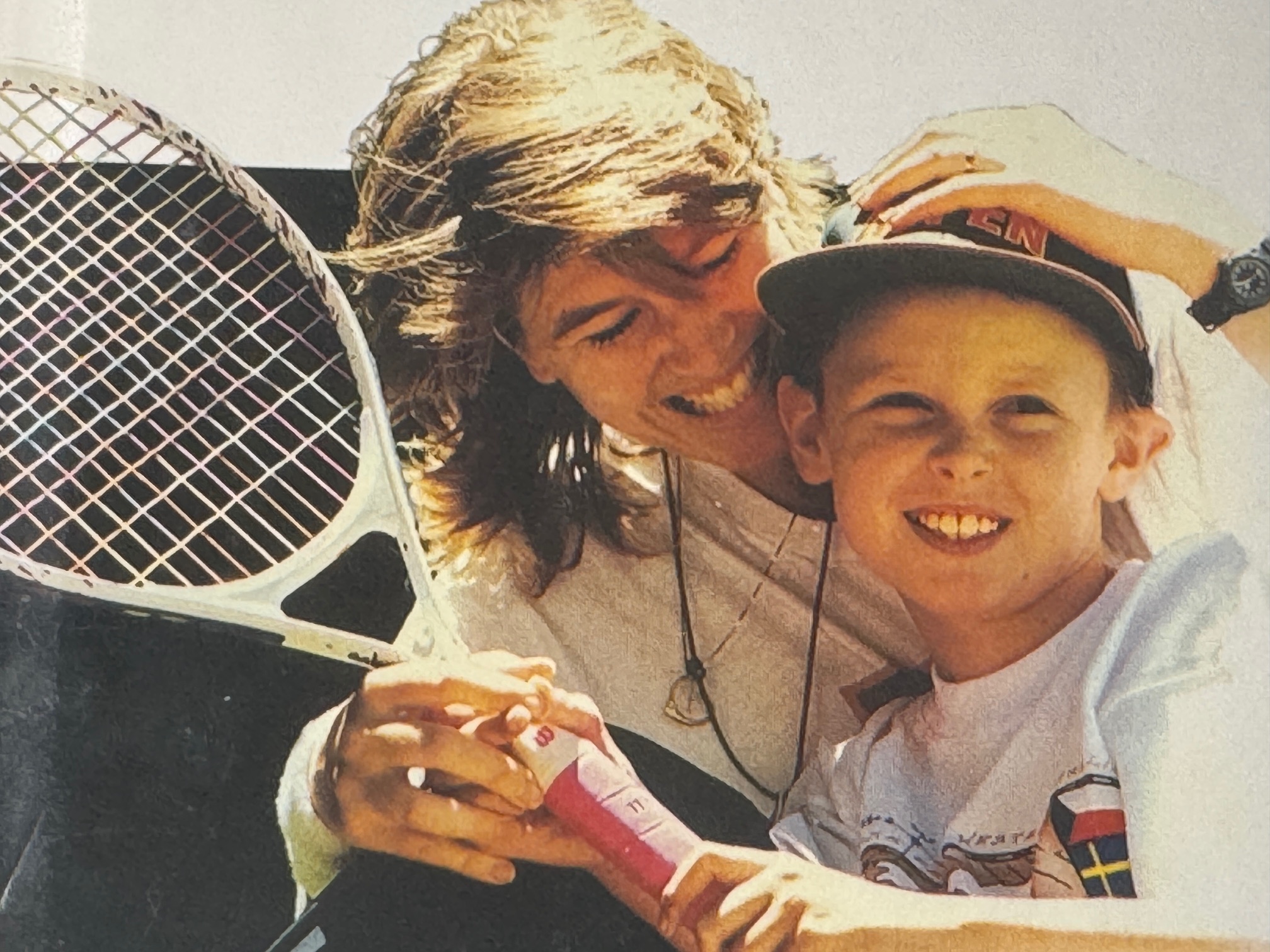

In Ladies of the Court, Jennifer Capriati had achieved stardom, but was clearly starting to spiral out of control. Her competitive bright spot in this book came in the Epilogue when she won a gold medal at the 1992 Olympics. Her resurgence during the Olympics was speculated to have been fueled in part of staying in the Olympic Village separated from her father and the rest of her entourage. Capriati didn’t go completely off the rails until 1994, but a careful reading of Ladies of the Court shows that the warning signs were apparent. (I previously wrote about some of Capriati’s challenges in “The Crazy Summer of 1994.”)

The allegations in Ladies of the Court is that many players were suffering under sexual, emotional, or physical abuse at the hands of their coaches, fathers, and brothers. Probably one of the most startling revelation in the book was the attitude from the organizations, including the USTA, that downplayed what was reported to be happening. When tracking down a tip Menshaw received about a USTA coach that had been fired for sexual harassment of players, he was essentially stonewalled by the organization. However, one source within the USTA confirmed that there was an incident and provided significant color around those events.

That USTA employee indicated to Menshaw that organizationally the USTA was more concerned about potential predatory lesbians than inappropriate relationships between players and their coaches. Later, Menshaw asked Martina Navatrolova a question at a news conference related to that assertion by a USTA Source. The USTA reponded by conducting a witch hunt in the organization to determine who said it. Failing to locate the source, the USTA wrote a letter to Menshaw warning him to not attribute any statements of the sort to the USTA in his forthcoming book.

All this returns me to the phrase that popped into my head when I started in on this essay. The tennis world including the USTA and the WTA has come a long way, baby. For me, Ladies of the Court was a challenging read primarily due to the disturbing nature of some of the content. At the same time, it is an important snapshot about where Women’s professional tennis was at the time. It is a story that needed to be told and remembered.

Fiend At Court participates in the amazon associates program and receives a paid commission on any purchases made via the links in this article. Additional details on the disposition of proceeds from this source are available in the “About Fiend at Court” page.

- Bring Me the Sweat of Gabriela Sabatini, Clive James.